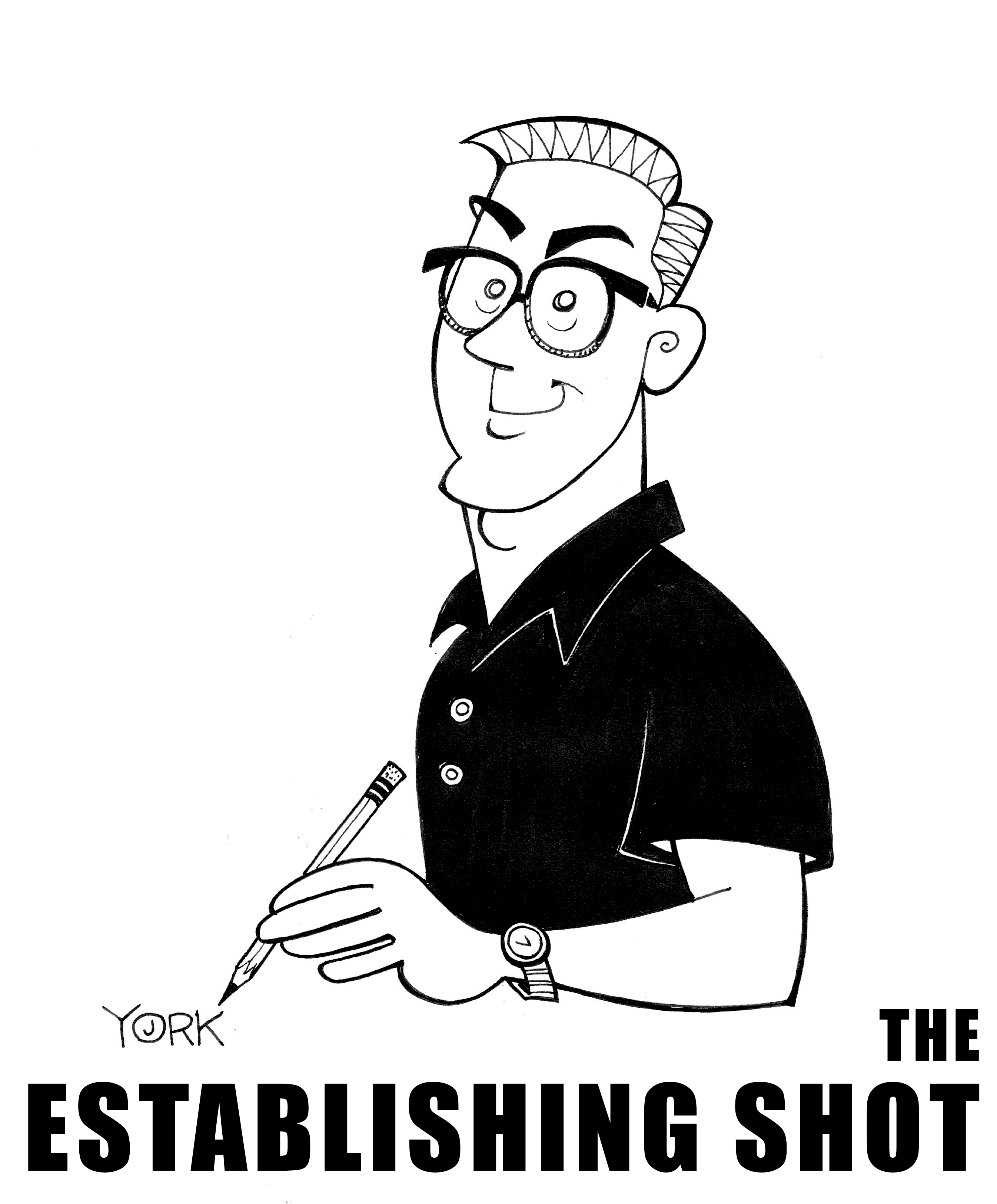

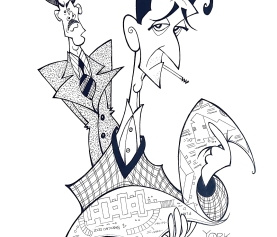

Original caricature by Jeff York of Bill Nighy in LIVING. (copyright 2023)

There are actors who leap off the screen with their larger-than-life approach to performing, and then there are actors who always carry a little more in reserve. Those who hold back, like the English actor Bill Nighy, compel us to move in closer, lean in to get more intimate, and that’s precisely what he does in the new character study LIVING. It’s the story of a quiet and reserved businessman in 1950s England who is at a crossroads in his life. Nighy’s work is so subtle and delicate, it’s a marvel of minimalism done for maximum effect.

A remake of Akira Kurosawa’s classic Japanese film IKURA, LIVING focuses on a mid-level bureaucrat in the public works department of London’s city government whose life is complacent and dull. Mr. Williams (Nighy) lives his life by rote. He wears the same kind of suit to work every morning, catches the same train, and makes the same small talk with his colleagues. Little distinguishes a Monday from a Friday in Williams’ world. His life is usurped, however, when he’s handed a fatal bill of health and given only 6-8 months to live. Suddenly, the cancer-stricken Williams must reckon with his mortality, and in addition, his legacy.

Such a story could have been a broadly dramatic one in an Ebenezer Scrooge kind of way with its protagonist changing his entire personality. But that really isn’t what happens in life, and this film aims to focus on the incremental changes that are still wholly significant for people like Mr.Williams, hopelessly stuck in a rut. While processing his predicament, Williams will come to the realization that he’s done very little living in his life and he will take some brave steps to step outside his incredibly constricted comfort zone. For such a modest man, that means taking baby steps: a few days off work, visiting the boardwalk, even drinking with a stranger while singing with other patrons in the pub. It’s not a lot for most, but for Williams, it’s colossal.

Returning home, the long-widowed Williams realizes that he doesn’t have the kind of relationship with his son and daughter-in-law that would allow him to easily tell of his misfortune. Instead, he sits down to a quiet dinner and barely mentions the meal’s Shephard’s Pie. Williams and his family are all part of the long tradition of British decorum. This film slyly indicts such stiff upper lips, critiquing English culture, just as the original Kurosawa film cast aspersions on Japanese culture.

Eventually, Williams does connect with someone – a young woman who clerked for him in the office. Margaret Harris (a wonderfully accessible Aimee Lou Wood) joins him for a drink one night and they start up an odd but affecting friendship. They bond, sharing a few meals and laughing over the humorous names the young woman has given to her former coworkers. She tells Williams that her nickname for him was “Mr. Zombie,” forcing him to realize all the more that he’s spent too much time in an inert form.

What Williams does with the rest of his days makes for the remainder of the story and it adds buoyancy to this sad tale. Nighy plays all of it with grace and sly wit curling at the corners of his mouth. Director Oliver Hermanus, working from an accomplished adaptation by screenwriter Kazuo Ishiguro, finds the poetry in Williams’s struggle – shooting, editing, and scoring it all with artful finesse. The film is never big, but the payoff at the end is surprisingly immense in its way.

The fact that a film this simple and affecting is only playing in cineplexes at present makes it all the more exceptional. Small stories deserve big screens too, and the muted changes in Mr. Williams’s life in his remaining days make for one of the better character arcs in cinema.