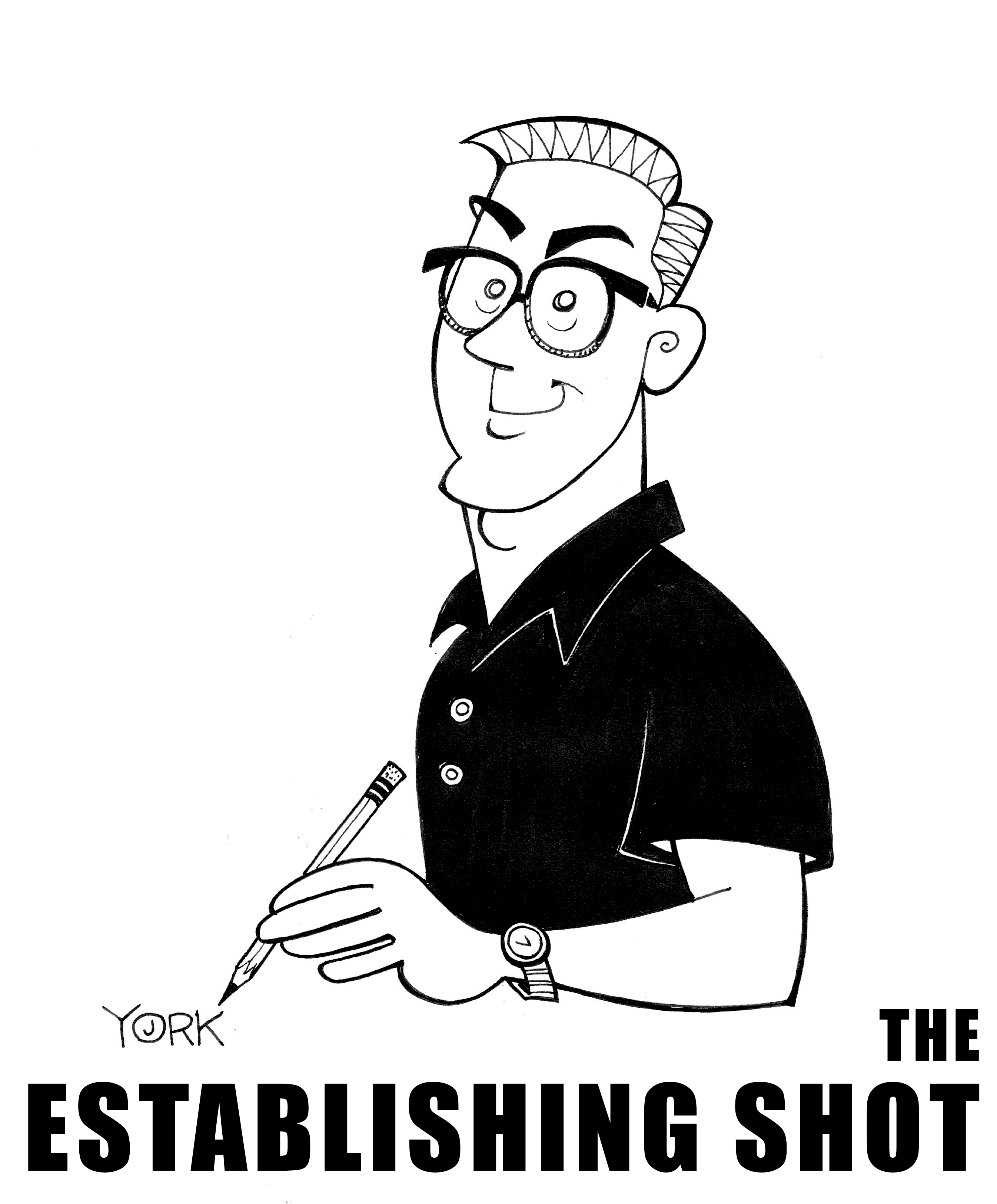

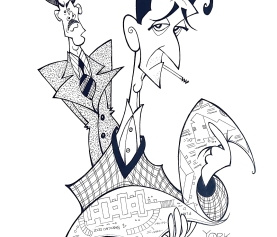

Original caricature by Jeff York of the principles of WOMEN TALKING: Claire Foy, Judith Ivey, Ben Whishaw, Jessie Buckley, Sheila McCarthy, and Rooney Mara. (copyright 2022)

Filmmaker Sarah Polley has pulled off a significant hat trick with WOMEN TALKING. Not only does her film boast the year’s best-adapted screenplay (which she wrote), but her cast is the best ensemble on screen as well. Ultimately, Polley’s film stands as one of 2022’s very finest, perhaps not the easiest to watch during the holiday season with its themes of rape and physical abuse, but it’s a searingly dramatic tale that demands to be seen by adults everywhere.

Based upon Miriam Toews’s 2018 novel of the same name, the story concerns eight Mennonite women who meet secretly in a barn’s hayloft to discuss their options after they’ve all been drugged and raped by the men in their closed community. Repeatedly. It is fiction, inspired by real-life events that occurred in an ultra-conservative Mennonite community in 2019 Bolivia. There, various male members of the colony raped female members from 3 to 65. Indeed, Toews kept many such facts featured in her prose as does Polley in her adaptation. It is shocking, for certain, and yet, not all that surprising given what men have done to women in every society since the beginning of time.

And yet, here are these heinous acts, as they so often are, done in the name of God, the State, or patriarchal principles. Wisely, Polley’s film chooses not to show anything but glimpses of the abuse, but the words shared by the women as they relate their stories are utterly harrowing. Even more dramatic is how riveting the actresses all make their character’s testimony. And, surprisingly, much of what their characters say is fierce, bold, and inspiring, as even women in such a conservative sect, rally together to prevent any further abuse.

Amongst the women debating exactly what actions to take are Greta (Sheila McCarthy), one of the eldest. Along with Agata (Judith Ivey), the other matriarch, they attempt to hold a sort of ‘town forum’ to democratically arrive at a response to their male counterparts. Do they choose to let it go, and do nothing? Or do they stay and fight? Or would they be better off leaving to ensure it doesn’t happen again? Soon, each of the pros and cons of these three courses of action will be debated with fire and zeal and it’s got the flavor of a great courtroom drama to it all.

The key women joining in the back and forth are Mariche (Jessie Buckley), Greta’s daughter, Ona (Rooney Mara), Agata’s oldest daughter, and Salome (Claire Foy), whose three-year-old daughter was even attacked. The others participating are Majel (Michelle McCloud), and teens Autje (Kate Hallett), Neitje (Liv McNeil). Each of these actresses is given a golden opportunity to shine, though rarely in a theatrical soliloquy kind of way. Instead, Polley has made their perspectives part of a bigger conversation, a rollicking discourse about the community, faith, matriarchy, and sexual politics. It’s an incredibly riveting conversation delivered by these religious women, who may be sheltered, but they’re no spring chickens. They know what’s going on and don’t mince words, even though speaking out in such a way goes against their communal beliefs.

Especially compelling are Buckley and Foy, channeling the most rage amongst the lot, but everyone here truly is their equal. Mara, ostensibly the lead, does subtly heartbreaking work here as a spinster who’s decided to keep her rapist’s child to ensure something positive comes out of such wretched events. Ona’s argument is just one of the ones presented here, and that God knows, is being argued about in every corner of America right now with the overturning of Roe and the peeling back of women’s bodily autonomy. Still, Polley doesn’t underline such issues as they are clearly prescient, and it’s a testimony to her skill as a filmmaker that she shows restraint where so many others might have hit such nails harder than needed.

Veteran character actors McCarthy and Ivey are wondrous throughout, building their characters mostly through reactions to the more livid around them. Adding crucial support, both in the story and to the film, is Ben Whishaw as August, a sympathetic teacher from the community they’ve asked to transcribe what they’re saying for a record of sorts, as none of the women are allowed to read or write in the conservative sect.

The words and such a cast would probably have been enough for most filmmakers, but not Polley. She brings a sense of the cinematic to every frame, never allowing the film to feel static, or like a filmed play. Instead, she shrewdly uses flashbacks to highlight various testimonies, and she opens up the action to outside and around the barn as well. Polley’s hire for the underscore was a smart move too as Oscar-winning composer Hildur Gudnodottir (JOKER) delivers one of the year’s best scores. It’s a slyly tense one, mixing bells, mandolin strings, and synthesizer tones in compositions that feel like the spiritual marriage of Jerry Goldsmith and David Newman.

Despite all the incredible qualities that the film showcases, it may be difficult for many to willingly sit down to such tales of rape and abuse. But these stories must be heard and the courage displayed by the women is more than enough to counter such hesitancy. You might even find the group’s conclusions inspiring as these were not just women talking but human beings choosing action and defiance over centuries-old tradition and complying with their station. To hell with that.