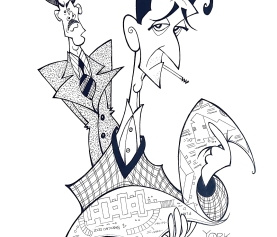

Original caricature by Jeff York of Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson in THE BANSHEES OF INISHERIN (copyright 2022).

Writer/director Martin McDonagh has always cultivated a very dark sense of humor in his plays and films, and in THE BANSHEES OF INISHERIN, such sensibilities may have reached their zenith. The story of two men in 1923 Ireland who stop being friends starts out amusing, then becomes hilarious, and finally veers toward the macabre. It’s a hoot and a half up until the last half hour when the comedy turns to tragedy, but make no mistake this is one of the year’s best films. It’s clever, challenging, symbolic, and impeccably acted by its stellar cast.

Colin Farrell plays Pádraic Súillebháin, a sweet, middle-aged farmer on the fictional island of Ishernin. An Irish civil war may be occurring on the mainland but it hardly disrupts Pádraic’s simple life. The same cannot be said for his best friend Colm Doherty (Brendan Gleeson). Colm is disturbed by it, along with many other things that bring him despair. Getting older, the limits of the ‘burg, and Pádraic are all starting to get under Colm’s weathered skin. One day, Colm up and decides to end his friendship with Pádraic, telling him that he’s bored with his friend’s chatter about cow poop and local gossip. Colm instructs Pádraic to never talk to him again even though they frequent the same pub daily and can’t help but run into each other at church and other places in their small town.

Pádraic is terribly wounded by Colm’s dismissal. He tries to cajole himself back into his good graces, but the more Pádraic talks, the more Colm seethes. Turning to his younger, wiser sister Siobhán is no help either as she advises her brother to move on. She too is antsy like Colm, bored and unsatisfied with the town and the townsfolk. Siobhán isn’t thrilled either with how her brother gives the farm animals the run of their small cottage, but her protests fall on deaf ears. He is especially fond of his miniature donkey Jenny whom he treats like a pet, and it’s easy to see why. She’s adorable and the animal actor is a scene-stealer if there ever was one.

Pádraic keeps coming at Colm, trying various ways to ingratiate himself. It only drives Colm to more anger, calling his former friend a “limited man” who doesn’t appreciate music, deep thinking, or any sense of legacy. Colm is so serious about severing his relationship with Pádraic that he threatens to cut off a finger every time he dishonors his wishes. From this point in the story, McDonagh quickly ratchets up the darkness in the comedy as the ‘battle’ between the friends escalates, turning their quiet little town into a war zone to compete with the fighting on the nearby mainland.

Throughout, McDonagh brilliantly savages not only macho male pride and Irish stubbornness but the viciousness of gossip and contradictions in the Catholic faith. McDonagh also cleverly mirrors his characters, not once, but twice. Siobhán herself is often a proxy for Colm’s frustrations with Pádraic. And the farmer treats his younger friend Dominic Kearney (Barry Keoghan) with a similar dismissiveness as he experiences with Colm.

Farrell and Gleeson give superb performances, both hilarious and heartbreaking. Expect both of them to figure prominently in the upcoming awards season. Condon should too as her performance as the film’s moral center is both sly and sweet. The supporting cast is letter-perfect, as is the cinematography by Ben Davis. He knows just how to make the countryside look both ravishing and stultifying. His images show off the lush countryside, make no mistake, but he also frames everything to be confining, with the rocks and the ocean rearing dangerously close to everything and everyone. The score by Carter Burwell underlines the story of these two childishly feuding men as well. It suggests a nursery rhyme, albeit one done in a minor key.

THE BANSHEES OF ISHERNIN is chock full of McDonagh’s rollicking dialogue and his pointed symbolism as well. He underlines the war between the main characters with small bombs continually going off in distance, and he adds a deathly presence to the proceedings each time the witchy Mrs. McCormick (Sheila Flitton) shows up. You may walk out of the theater stymied, or even disturbed by how quickly the laughs turn into gasps, but that’s what McDonagh is after here. And he wants us to think about his story long after the final credits roll. There’s a lot to unpack here and McDonagh is just the kind of thinking man a guy like Colm would want to have a pint with and chat.