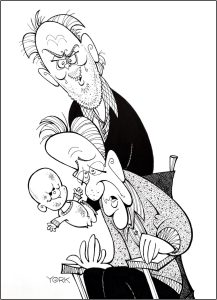

Original caricature by Jeff York of Geoffrey Rush and John Lithgow in THE RULE OF JENNY PEN (copyright 2025)

The late, great Bette Davis once said, “Old age ain’t no place for sissies.”

THE RULE OF JENNY PEN, the new film from New Zealand filmmaker James Ashcroft proves that adage long before any tried-and-true horror tropes make their way into the story. The truest horrors in the film show up as soon as Judge Stefan Mortensen (Geoffrey Rush) enters a nursing residence after having a stroke while rendering a sentence in his courtroom. Nursing homes as the last stop before death for the elderly can terrify as much as any haunted house.

Such residences aren’t always permanent as some patients recover from a stroke or health issue and return to the outside world. The judge arrogantly believes he’ll be one of them, even though he’s bound to a wheelchair and has lost the use of his right arm. Because of his pride, Mortensen talks down to the staff and sneers at the more encumbered patients around him. He’s right to feel put upon in many respects as the dull, depressing surroundings hardly are life-affirming. Most residents there shuffle about like zombies, the meals and activities are boring, and having to be bathed by attendants is utterly humiliating. Until his release, however, Mortensen is stuck in the chair, and it’s made him even more of a prickly pear.

Mortenson makes matters worse by instantly alienating his roomie Tony Garfield (George Henare), a once professional rugby player. He lobbies insults towards him and soon enough, all the judge’s arrogance rubs resident Dave Crealey (John Lithgow) the wrong way. Crealey is a former employee who knows the ins and outs of the facility like the back of his hand. Because of such know-how, the still limber and towering Crealey lords his superiority over the others there, and it becomes apparent that he and Mortensen are headed towards an old man a mano.

Crealey leans into psychotic tendencies at times which manifest in his use of a hand puppet used to rule over the other patients with an iron fist. It’s a filthy old thing, with the head of a baby doll whose eyes have been hollowed out. It’s plenty ghoulish just to look, even more so when Crealey assumes the voice of his beloved “Jenny Pen” and orders the residents to “lick her a**hole” to heed her rule.

From this premise, the psychological horror tropes kick exponentially as Crealey decides to menace Mortensen not just with Jenny, but via a game of cat and mouse both terrifying and unseemly. (Crealey’s first move is to douse the judge with a pitcher of urine.) Hard to get the upper hand when you only have one that works, but the wily Mortensen still has tricks up his sleeve. The fun of the film comes from watching these two go whole hog at each other even though they’re incapacitated and limited by frail health. In many ways, it feels like SLEUTH or WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE played out in an old folks’ home.

All of this could come off as silly hijinks in the wrong hands, but both actors treat the material seriously. Rush and Lithgow give superb, wholly committed performances. It helps too that the script by Ashcroft and co-screenwriter Eli Kent is written in equal measures pulp and pathos, honoring the intentions of Owen Marshall’s original short story they’ve adapted. Crealey may be a creeper but he’s not unsympathetic, and Lithgow imbues his baddie with sprinkles of childish vulnerability. Rush ensures that Mortensen remains pitiable too, underlining even his most sarcastic asides with a bit of a smile. He’s especially remarkable in an early scene where the judge almost drowns in a bathtub while his attendant is away. It’s scary as hell and proves that losing one’s faculties is the evilest villain here.

Ashcroft tends to overdo a cocked camera angle or two and an overly loud sound cue here and there, but his film is remarkably unsettling from start to finish. And while this disturbing tale is pitch black, it’s extremely inspiring as well, considering that its two leads are both septuagenarian actors. The elder men in the story may be striving for relevance in a world that’s abandoned them, but it’s thrilling that the film world still embraces talents such as Rush and Lithgow wholeheartedly.