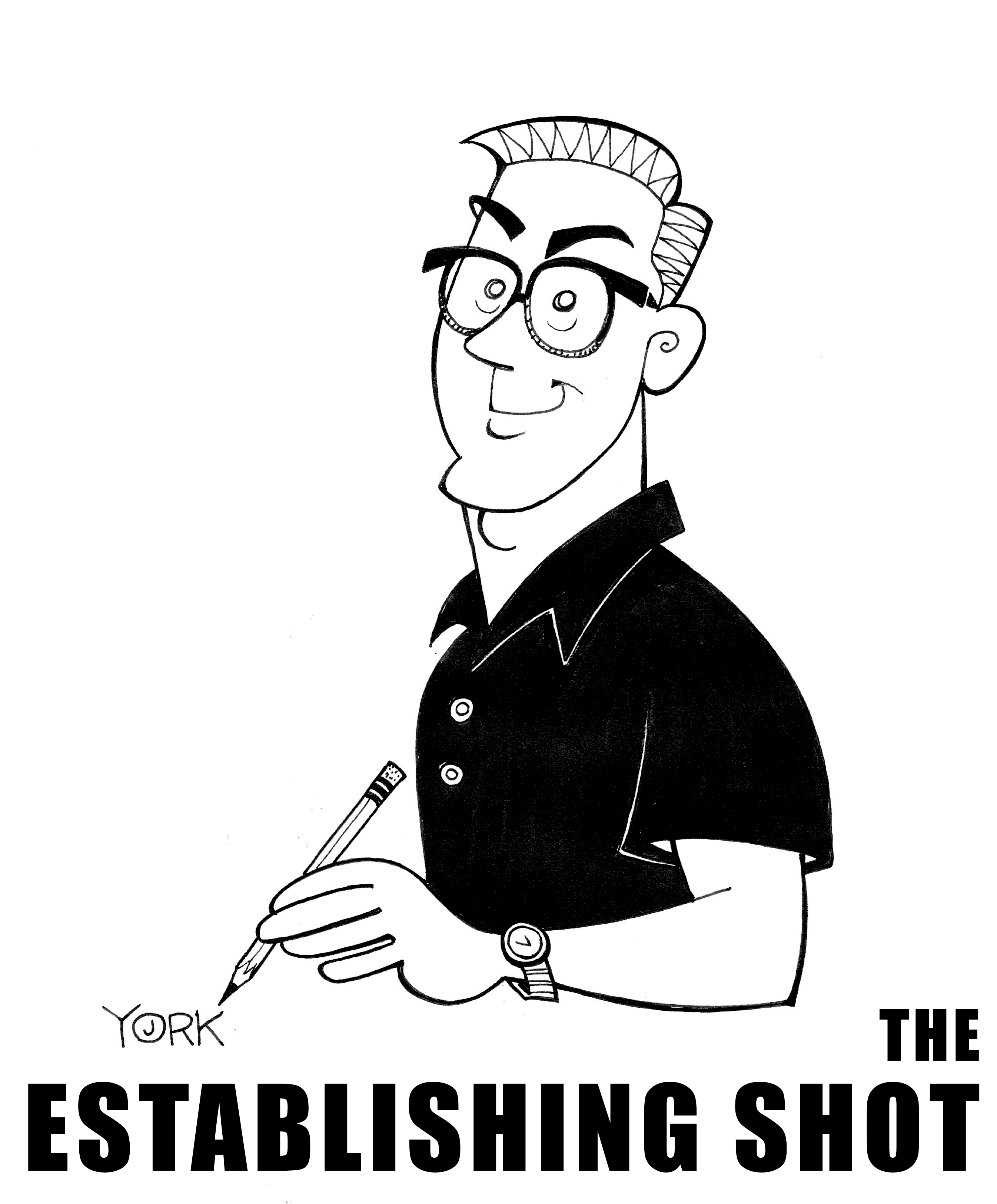

Original caricature by Jeff York of Anya Taylor-Joy in EMMA. (copyright 2020)

Mister Webster defines the word baroque as “ornate, fancy, and very elaborate” with the words curlicued, showy, and wedding-cake thrown into the description for good measure. I cannot think of a better word than baroque to describe the new big-screen version of Jane Austen’s classic novel EMMA. It’s art directed within an inch of its rococo life, costumed as if by peacocks, and acted with enough verve to play to the second balcony. It’s often quite fun and funny, but it’s so filled with largesse, it feels more like a caricature than a romantic comedy. (I cannot think of a film review of mine screaming out for a caricature illustration to accompany it more than this one!)

The broadness of this new EMMA, directed by Autumn de Wilde, from a screenplay adaptation by Eleanor Catton is apparent from before you walk into the theater. The theatrical posters showcasing star Anya Taylor-Joy depict her standing in front of a painted backdrop, staring right at the camera with an expression that seems too satirical by half. Taylor-Joy, thankfully, doesn’t deliver a performance that coy. (Her considered performance isn’t that much different than the star-making turn of Gwyneth Paltrow in the 1996 adaptation of EMMA.) Still, despite Taylor-Joy’s restraint, almost everyone around her, as well as the settings, props, and costumes, seem to be wholly unrestrained. It’s unsettling at first, an adaptation pitched so high that you wonder if the film will ever simmer down.

It never does entirely. Almost every room, be it a study in a mansion or a lady’s shop, subscribes to the idea that more is more. Virtually all the female costumes are so fussy, ornate, and adorned, they push towards the absurd. Nothing looks particularly lived in either. Even the poorer characters have immaculate lapels and clean boots. Clearly, a hugely theatrical version of the property is what director de Wilde was going for, and maybe that’s the point. The material is hardly new. It’s all so precious in its way to begin with, what its preoccupation with matchmaking and the societal fall-out of a poorly chosen quip, that it maybe needs some commentary on such inherent absurdity. If directors can do modern-dress Hamlet to suggest the business world is as cutthroat as the Danish prince’s time, why can’t a filmmaker turn a twee rom-com chestnut into something as absurd as its mannered world suggests?

Well, for starters, it’s actually a misread of the material. Austen’s world is certainly a quaint and unrecognizable one by at least two centuries, but her themes of women striving for position and power within the confines of the male world are not. Indeed, EMMA has always been one of Austen’s most forward-thinking works due to its title character being the one who pulls all the strings in the story. She also fixes the messes she makes and avoids being overly punished for her sins by the patriarchal society. Emma also manages to ultimately help other women along the way, rather than destroy them so that she may prevail. If those aren’t themes of feminism and equality that comment relevantly on our modern times, I don’t what does.

So why the cartoonishness? The director has sly veteran character actor Bill Nighy literally jumping into scenes, not to mention coaxing the wonderfully talented Miranda Hart to blubber so much in every scene that she might as well be underwater. The editing and the musical cues seem far too arch as well, feeling more like those from a Blake Edwards farce. That the story manages to come through at all is a credit to Austen’s prose and Taylor-Joy’s refusal to play too broadly or even ask for sympathy. In fact, her Emma may be the coldest and rather villainous portrayal of the role yet on screen. (Indeed, the character can be read as the baddie, what with all of her meddling and manipulation for selfish gain.) Taylor-Joy never gets lost in all the plumage and buttons, managing to telegraph Emma’s worries, uncertainties, and remorse with her marvelously expressive eyes and nuanced carriage.

For those not familiar with Austen’s classic, they may find this to be fine, flighty fare. Indeed, Austen was ahead of her time, poking fun at the class system, sexism, and entitlement, and that comes through here quite vividly. But because it does, it doesn’t need all the extra effort straining so around it.