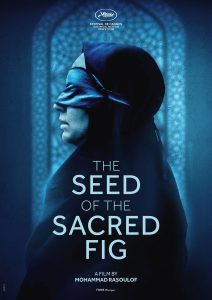

The actual story behind the new Mohammed Rasoulof film THE SEED OF THE SACRED FIG may be more interesting than even the movie’s powerful narrative. The accomplished Iranian filmmaker had already been arrested by his nation’s government for previous films and the secretly-made THE SEED OF THE SACRED FIG got him sentenced to eight years in prison by Iran’s Islamic Republic earlier this year. Miraculously, Rasoulof was able to escape to Germany to be able to continue as an artist, and in addition, see his bold film become one of the highlights of this year’s 60th Chicago International Film Festival.

The story concerns the family of Iman (Missagh Zareh), a Tehran lawyer whose true-blue belief system has put him in the position for a big promotion within the revolutionary court. He’s cautiously optimistic even though his first task is to approve the death sentence of an accused man he’s not been able to investigate properly. His loving and supporting wife Najmeh (Soheila Golestani) doesn’t dwell on his moral conflicts, but on what will come with his new gig: prestige, a better apartment, and other perks benefitting them, including their two teenage daughters.

College student Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami), and high schooler Sana (Setarah Maleki) don’t even know what their father does for a living as such government vocations are hush-hush. They also have no idea that he has brought a gun that he has brought home from work that he must now carry while on the lookout for “enemies of the state.” Students are protesting all of the ancient rules and restrictive laws that don’t jibe with the modern world and the streets are full of skirmishes with government officials and police. The complications are not further enhanced by the fact that both of his daughters are feisty, modern thinkers, and they often challenge their parents. To add fuel to the potential fire, one of their besties is Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi), a forthright student unafraid to openly talk about protesting and preventing the overrun of the Tehran campus.

Of course, violence will soon come to the doorstep of their apartment when Sadaf is injured during a campus battle with police. The compassionate Najmeh lets her into their apartment to tend to her wounds, despite misgivings about the protests, and her actions endanger Iman, his family, and his new job. Things spiral out of control even more as tempers flare, family loyalties are questioned, Iman is forced to cover his family’s tracks at work, and everyone starts wondering just whom they can trust. Oh, and that pesky weapon he brought home somehow disappears too. Did he forget where he put it or did one of those closest to him hide it?

All of this makes for intense drama, obviously, but where the film succeeds even more than in creating a crackling mystery about a missing gun is in how it showcases the deterioration of Iman’s family. You may even find your alliances shifting between family members as you watch it all play out, liking one more than you did before, and vice versa. That’s entirely Rasoulof’s point. He’s making the point that a ruthless state only creates victims.

Such messaging comes through loud and clear, but the filmmaker applies a lighter touch to most other aspects of his storytelling. The performances feel painfully real, the action looks utterly authentic, and it’s all shot on location in Iran, plus the terror created is enhanced by intercutting actual cellphone footage of state police atrocities in the streets. The closest Rasoulof gets to cinematic flourishes can only be found in a few slow-motion shots here and there, and the clever foreshadowing he applies in the first half hour. My favorite bit was when he shows Najmeh manicuring Rezvan’s eyebrows in an early scene, and then uses a similar close-up later to show her removing buckshot from the cheeks of the wounded Sadaf.

It all makes for a compelling, character-driven piece about the toll of violence, the overreach of totalitarian governments, the power of protest, and a modern world that simply is not going back. While not the easiest film to sit through, and one that probably could’ve trimmed 20 minutes off its 2-hour-48-minute run time, it is a movie for our time, up to the moment, and braver than most art ever can claim to be. Bravo, Mr Rasoulof. And stay safe.