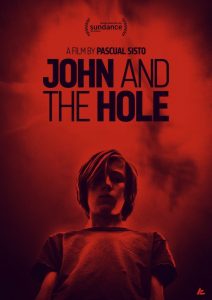

Movies and television shows have always gone out of their way to promote the idea of family. Even in action-adventure films like the FAST & FURIOUS franchise, Vin Diesel waxes on and on about the importance of it. (Really? Family ranks above those souped-up cars?) And while most of Hollywood is content to present a rather Pollyanna-ish view of mom, dad, and the kids, Spanish filmmaker Pascual Sisto doesn’t see the American family unit the same way. In his debut film JOHN AND THE HOLE, Sisto examines the dysfunction of family and how such units can so easily fall into tedium, miscommunication, hostility, and sociopathy.

The hole in the title refers to an abandoned shelter in the backyard of a lush home out in the woods, but it also describes the emptiness in the soul of the homeowners’ 13-year-old son John (a superbly serene Charlie Shotwell). His parents Brad and Anna (Michael C. Hall and Jennifer Ehle) are an affluent couple, living in a large, modern house on a few sprawling acres of surrounding woods. They have a pool, expensive furnishings, and carry themselves with the laziness of the rich and entitled. Brad and Anna don’t seem like whole people any more than John does, and only their teen daughter Laurie (the ever-luminescent Taissa Farmiga) seems fully present most of the time. She’s so hungry for any kind of genuine human connection, she can’t wait to escape the dull family dinners to go hang out with a boy she barely knows.

But on the surface, these four seem like a lovely, all-American family. John certainly goes through the motions of being a normal teen. He skateboards, banters profanely with his friends during video games, and aggravates his sister via his irritating habits. But he’s blank, showing little emotion, almost entirely non-plussed in any situation. With his floppy hair sloping down his forehead and his lanky body stooped over as if he can barely summon the energy to stand up straight, John suggests a young Jeffrey Dahmer. Indeed, strains of psychopathy found in that famed serial killer will soon become apparent in young John.

For starters, the boy becomes obsessed with the abandoned shelter that the property’s previous owners never completed. He even breaks his sulking silence to ask mom and dad about it. Then, given no real provocation, John drugs each family member one night and carts them via wheelbarrow to the 25-foot shelter. He deposits them into the hole, and as they wake the next morning, they realize their predicament and worry that some deviant is now holding them hostage there. How right they are.

Not long after, the dead-eyed John shows up and stares at his pleading parents. He says nothing, leaving them behind to return to his home and start living an undisciplined life without adult supervision. It’s a modern-day version of THE LITTLE GIRL WHO LIVES DOWN THE LANE where a dangerously clever child cons family and community while holing up in the home. John proceeds to eat what he wants, drive his family’s car about, and steal their money from the ATM to pay for his new lifestyle.

But even though John experiences freedom for the first time, he shows no joy in doing so. He even likes to hold in breath in the pool as if to taunt death. Meanwhile, his family gets dirtier, hungrier, and more depressed as their days turn into weeks. John stops by occasionally to feed them, but almost no conversation takes place. John’s walls are up almost as high as those of the unclimbable prison he’s put his family in.

Director Sisto delivers scathing commentary on the modern-day family’s inabilities to connect. These four were living life by rote, and even when he’s home alone, John still goes through the bland motions of what life is supposed to look like. Sisto, and Nicolas Giacobone’s searing, knowing script, don’t let society off the hook either. The neighbors and police who stop by looking for the family end up acting oblivious too. It’s as if everyone on screen is sleepwalking through life and Hall and Ehle, in particular, are experts at essaying such remoteness. Even John’s barking tennis instructor misses the fact that John is swinging lifelessly at tennis balls as if he’s on robotic autopilot.

The obliviousness continues, even in that awful hole. Brad, covered in soot after many days and nights there, still tries to talk his wife into fornicating even though their daughter is mere inches away. Laurie pines for her classmate even though death may be calling on her much sooner. And John heedlessly echoes the squalor of the hole by turning his once immaculate home into a pit filled with discarded pizza boxes and dirty clothes. The film is a darkly comic one as it finds humor in such parallels.

Perhaps it’s in the timing, but Sisto’s film couldn’t be more relevant to what’s going on in America during this summer of 2021. After going through the ordeal of COVID-19 for 18 months, being stuck in our own holes for the better part of it, too many Americans are still as oblivious as those in the film. Almost a third of our nation’s citizenry refuses to get vaccinated to enable the horrors of the pandemic to be behind us. Sisto’s film, intentionally or not, scolds us for our own self-destructiveness and naive self-absorption like the family in JOHN AND THE HOLE. Such synergies may be the most frightening aspect of this tense, deliberate, and disquieting film.